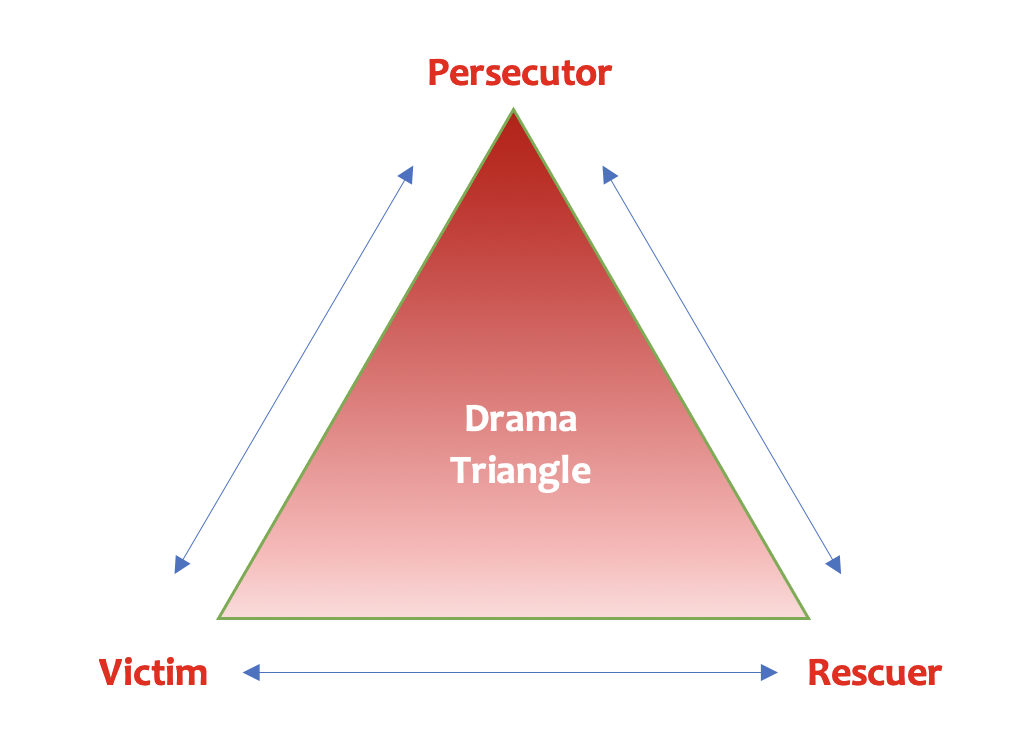

Stephen B. Karpman’s drama triangle represents a pattern of dysfunctional relationships. It can exist in domestic situations and in the workplace too.

Picture a three-sided boxing ring, with one person in each corner. In one corner is the Perpetrator (aggressor) who is acting out with anger or passive aggressive behavior; in another, the Victim whom this is directed against. The two sides are locked into an unhealthy give-and-take. In the third corner is the Rescuer. This person sees the dysfunction and believes they can save the Victim. By inserting themselves, they complicate the dynamic. This is the drama triangle, described by Stephen B. Karpman as a pattern of dysfunctional relationships.1

While we are immersed in one of those three roles, it’s difficult to recognize it is happening to us. Our anger (whether as Persecutor, Victim, or Rescuer) helps us to feel self-righteous in whichever role we are assuming.

Persecutor: You deserve my disdain. You should be punished. It’s your fault. Victim: I would do better if I could. I try so hard and nothing I do works. I’m helpless here. Rescuer: He’s a dog. Let me get you out of there. |

The roles are not fixed. In many cases, people may switch roles in the blink of an eye. Those in the drama triangle easily switch from one role to the other, dynamically locked in an unending cycle of conflict as they rotate from one role to another, vainly seeking resolution of their pain.

Round 1: Perpetrator (father) attacks Victim (Mari) while Rescuer (husband) intervenes The extended family has been looking forward to this vacation for quite a while. Unfortunately, as often happens, Mari and her father begin arguing. “You are having babies instead of finishing college. You are wasting your life!” he shouts. Mari bursts into tears and her husband snaps. “Excuse me, sir, but I cannot sit by and let you continuously tear down my wife. Look at how you upset her. She always cries after you talk about how she is wasting her life. She’s a wonderful wife and mother and she means everything to our family. You are so arrogant you can’t see what you’re doing to her.” |

Round 2. Victim (Mari) becomes perpetrator. Rescuer (husband) becomes Victim. Perpetrator (father) becomes Rescuer. Mari to husband. “What’s wrong with you? Have you lost your mind? Don’t attack my father like that. He’s just trying to help me. He just wants me to be happy and successful!!!" Mari’s husband, “You’re my wife. Why are you jumping on me? So you are going to turn on me now!??” Mari’s father: “Mari, let’s go sit outside. He has no right to interfere with us. Let’s get away from here.” |

Round 3. Rescuer (husband) becomes perpetrator. Perpetrator (father) becomes Victim. Victim (Mari) becomes Rescuer. Mari’s husband to her father: “Your daughter may put up with insults from you but I won’t. Your arrogance and abusive behavior toward my wife is unacceptable.” Mari’s father to her husband: “I’m only trying to help my brilliant daughter achieve her potential and realize her dreams. You’re trying to make me the Victim here with your insults.” Mari to husband: “He’s my father. I understand him and know what’s in his heart. Nobody asked your opinion! Stop attacking him!” |

This is the template of a drama triangle. It doesn’t matter what role you assume when you first enter. Once you are in it, you can pivot to any role, all while protesting that the others are the ones at fault. The tension keeps the triangle in place. Only by recognizing the pattern and refusing to stay entrapped in it can there be hope for change.

How does this play out in the workplace?

Think about a work situation where everyone seems stuck.

The boss (Carmen) walks into the meeting room. She starts by attacking the people who didn’t do what she wanted, exactly as she wanted, when she wanted it (Perpetrator). Staff meekly apologizes, swears they will do better next time (Victim). One of the members, who has not been there long enough to learn the dynamic, tries to be a peacemaker (Rescuer). She politely questions the way feedback is offered. One staff member jumps all over her (now they are the Perpetrator). “She’s trying her best. We welcome her setting a high bar..!” Carmen glares at the interloper and those standing around watching. “Who are you to tell me how to manage?” (now she is the Victim). Everyone feels attacked and newbie starts looking for another job. Carmen (boss-Perpetrator) retaliates by giving her a bad review, and everyone goes back to their familiar pattern. |

How does this play out in the political divide?

January 6, 2021, was a watershed moment for American democracy. A large group of angry, frustrated Americans attacked the Capitol, believing themselves to be patriots righting a wrong in an allegedly stolen election.

Much of the population considered the rioters to be perpetrators. One author compared them to domestic violence abusers: “Those of us in the field of domestic violence recognize the behavior of the insurrectionists: their need for power and control, their sense of entitlement, their appetite for destruction, and their false sense of Victimhood.”[2]

Yet the insurrectionists saw themselves as Victims of a corrupt system. The New York Times reported, “In the eight months since a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol, some Republicans have tried to build a case – belied by the facts – that the vast federal investigation of the riot has been essentially unfair, its targets the Victims of political persecution.”[3]

Rep. Paul Gozar (R-AZ) testified at a Senate hearing investigating the insurrection, “Outright propaganda and lies are being used to unleash the national security state against law-abiding U.S. citizens.”

Rep. Hank Johnson, Jr. (D-GA) commented in a tweet that the attackers were portraying themselves as Victims:[4]

In many cases, perpetrators lash out because they feel powerless and victimized themselves. They regain an illusion of power by watching the other person suffer, and then justify their actions. A friend of mine acknowledged that in his younger years he would sometimes cold-shoulder friends or colleagues, just for the enjoyment of watching them squirm and suffer. It gave him a sense of personal power. Kyle Rittenhouse ran into a demonstration in Kenosha, Wisconsin, brandishing an assault rifle, and shot three men (two of whom died). He attributed violence to all demonstrators, while feeling his own was justified. To both my friend and Kyle, the ends justified the means.

Similarly, the Victim may have good reasons for feeling powerless. They see limited or no options for themselves other than enduring the situation. Both the Persecutor and the Rescuer reinforce those feelings – first, by telling the Victim they are to blame for the persecution, and second, by implying that they alone can save the Victim.

The Rescuer reinforces the situation by failing to see or acknowledge the vulnerability of the Persecutor and the submerged power of the Victim. Instead they join the Persecutor and Victim in seeing each of them in one-dimensional terms.

By focusing on immediately apparent behavior and interpreting that behavior in a vacuum, they simplistically view one another through stereotypes, not as complex individuals capable of more appropriate behavior. The result: a pattern of wasted energy, full of self-justifications. What they see is what they get.

Several cognitive biases are at play here. Under duress, our perceptions narrow and focus on what’s negative about the immediate situation. We fill in the gaps with stereotypes based on our histories and memories. This combination of selective perception and negativity bias limits our choices of how to respond and reinforces our assumptions (confirmation bias) that the other person is not acting in good faith.[5] Once someone is viewed as a Perpetrator (or Victim or meddling Rescuer), everything they do is seen through that lens.

Mari’s husband sees a bullying man, not a father concerned about his daughter. Mari’s father sees a man interfering with his relationship with his daughter, not a husband concerned about his wife. Mari sees a man who doesn’t understand her father and is attacking him, not a husband who loves her and wants to protect her. |

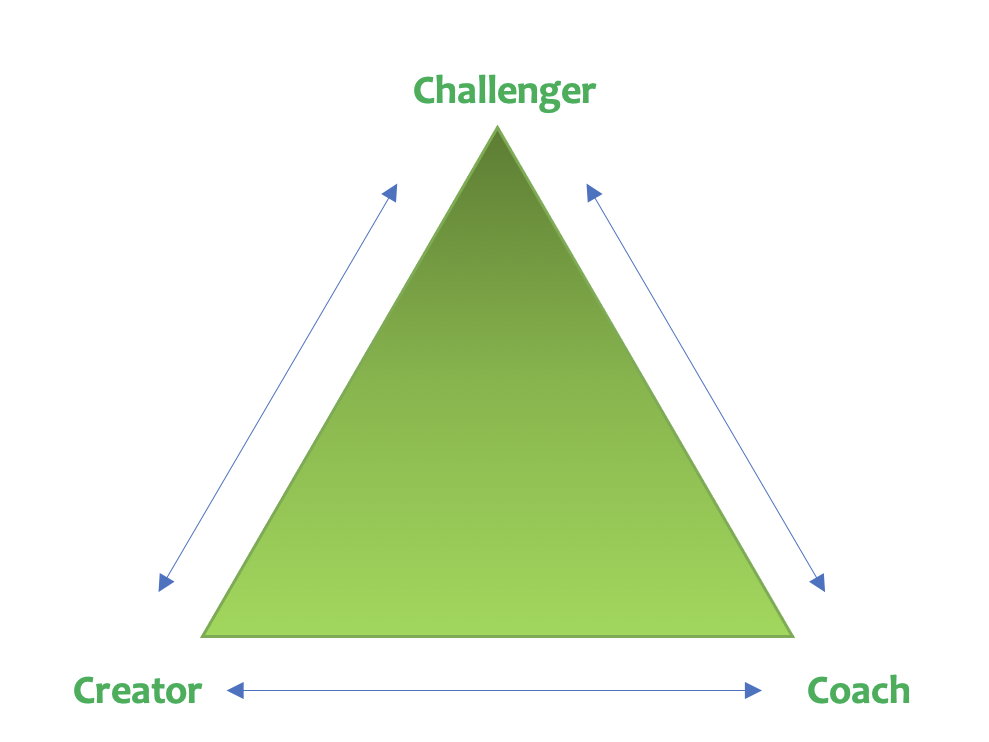

When we are red-hot angry or in the throes of defeated hurt, it’s hard to imagine the healthy side of the roles we have adopted. David Emerald drew a picture of what these could be in The Empowerment Dynamic.[6] From an Empowerment perspective, the Victim is transformed into a Creator, the Persecutor emerges as a Challenger, and the Rescuer becomes a Coach.

Replacing the Victim is The Creator: The Victim is stuck in the image of what she does not want to see happen. Mari wants her father to stop putting her down and her husband to stop picking fights with her father. Her focus on what’s missing from them helps keep her stuck. Replacing the negative with the positive is hard for many people. They don’t dare think of what might be, fearing it would never come to pass. If Mari dared (or was helped) to step into the Creator inside her, she would focus on her desires for her father to see the wonderful family she has created and the love they all share. If she could allow herself to really feel this, she might be encouraged to take steps in that direction.

Replacing the Persecutor is The Challenger. Mari’s father is also stuck. His anger possibly conceals his grief about the daughter he thinks he has lost and self-blame that he failed in raising her to become who he wanted her to be. The Challenger would focus on the love he is feeling for his daughter, his own unacknowledged guilt, and with support could possibly allow himself to be vulnerable with her and express appreciation for her as she is. Only then might she be receptive to his challenge for her to fulfill the potential he believes she has.

Replacing the Rescuer is The Coach. The coach regards the Victim as capable, creative, and resourceful. Without blaming or shaming, Mari’s husband could encourage Mari to gain clarity about her own strengths and what they want to create in their lives together. The Rescuer-as-Coach could ask Mari questions about what she values in her present life and the type of relationship she wants to have with both him and her father. He would likewise let the father know that he (the Coach) recognizes the love the father is expressing, however inappropriately, and support the father in developing a relationship with his daughter that allows them both to openly show they value themselves and each other.

Regardless of the role we find ourselves in, our first job is to stop and reflect. What are we doing in this situation? Who are we? Is the dynamic getting better or worse as a result of our efforts? Recognize when we are reacting from within the drama triangle based on our cognitive biases. We can’t step outside of the drama triangle until we recognize we are caught in the swirl of it.

I remember trying to save one of my relatives from a verbally abusive partner and becoming so angry and insulting toward him that he ordered me out of his house. How did I, the Rescuer, suddenly become the Persecutor/abuser toward the real Persecutor and abuser who was now feeling victimized and demeaned by my wrath? I knew about the drama triangle, yet not until I was back in my car, spitting mad, did I realize that I had become entangled in one with them.

Next, recognize everyone in the triangle has the potential to use their personal power more effectively. My relative had agency, even if she felt helpless against a dominant partner. She was highly respected at her job and knew in that setting she displayed her many strengths. I also knew her partner had the power to reassess his actions and take a less inflammatory approach. I had seen him express his vulnerability every now and then and knew he loved her with all his heart.

As Rescuer-turned-Coach, I had the power to be a catalyst for their growth, rather than an inadvertent reinforcer of their destructive dynamic. They both respected me and knew that I knew what it takes to have healthy relationships. I could have resisted the temptation to serve as the savior and instead provided humble support and coaching. This was several decades ago and I didn’t have it in me to do it.

I know now that the key was to decide to be effective rather than right [see blog #13, Would you rather be right or effective?]. I was right about the verbal abuse I witnessed. Yet I was not effective by viewing them both through the simplistic lens of Persecutor vs. Victim. Reflecting on the situation now, years later, I can see the potential for change in both of them that eluded me then. To quote Harriet Lerner, “We cannot make another person change his or her steps to an old dance, but if we change our own steps, the dance no longer can continue in the same predictable pattern.”[7]

The choice is to look forward to the potential for a positive future or backward to what should have been. Looking forward helps us adopt humility. We may have to amend our certainties about the situation and instead imagine a better future for all. Looking forward to a better future allows us to substitute respect for contempt – respect for everyone’s ability to speak up for themselves; respect for all contributions; and respect for feedback.

Looking forward sets the stage for us to be the change we want to see.

Questions to ask yourself

|

We are a leadership development firm that helps people and organizations create resilient, sustainable, multicultural, and inclusive settings. The ability to lead consciously can help you gain true awareness and earn the respect and trust of others.

It’s the assumptions we have about people’s lives that are the biggest obstacles to growth, awareness, and success. We help you understand how those assumptions are preventing you from becoming the best you can be as an organization, an inclusive leader, and a person.

[1] Karpman, S. B. Fairy tales and script drama analysis. Transactional Analysis Bulletin, 1968, 7(26), 39-43.

[2] The Link Between The Capitol Insurrectionists And Abusers

[3] Feuer, A. Debunking the Pro-Trump Right’s Claims About the Jan. 6 Riot. The New York Times, Sept. 27, 2021.

[4] Hank Johnson's Facebook post.

[5] Wikimedia.org, The Cognitive Bias Codex

[6] Emerald, D. The Power of TED* (*The Empowerment Dynamic). Polaris Publishing Group, Oct. 2005.

[7] Lerner, H. The Dance of Anger: A Woman’s Guide to Changing the Patterns of Intimate Relationships. William Morrow & Company, 1985.